The Definition of Consciousness

Me, I, My and Us, the MIMU of Self

BY LYNARD – NOVEMBER 2020

Defining consciousness is apparently not as easy nor straightforward as most of us assume. It is referred to as the “hard problem” for a reason.

Some terms we might casually through out to describe conscious:

- ■ attention

- ■ focus

- ■ awareness of self

- ■ awareness of place and time

These are all attributes of consciousness. They do not define consciousness. Nor do they describe how it arises from being human. There is another term, “subconscious” that comes close to hinting at what we mean when we want to describe consciousness. A subconscious implies that there is a self that is aware yet hidden, so awareness of place and time becomes an awareness of self also. The circular reasoning here leads nowhere.

The popular definition of consciousness encapsulates all the above attributes which essentially states that consciousness is being awake and being aware of the environment in which we find ourselves. Note that this definition does not encompass any action a living or artificial entity takes as a result of being conscious. This might, if we are to be exact, raise questions about the type of actions which should be considered in defining consciousness.

Expanding Attributes of Consciousness

When we add the dimension of activity into the assessment of consciousness, we start looking at other qualifiers, the most important of which is independent agency. While ants seem to be programmed (biologically) to exhibit ten or fewer activities throughout their life cycle, we generally assume none of those activities are the result of independent decision making on the part of any one individual ant. Dogs on the other hand may seem to exhibit hundreds of activities, some unique to dogs. Not all of those activities are the result of instincts governed by biology but there is a lot of simple response-reward activity that can easily appear to be independent activity to the semi-observant.

To any useful definition of consciousness we add the criteria of independent activity. A more inclusive description of independent activity is independent agency and is really critical to any definition of consciousness. A conscious being has all the appearance of being an independent agent. This brings us to Rene Descarte’s (1596 – 1650) and his declaration:

I think, therefore I am.

And this is where all our modern-day problems with defining consciousness began and why it became David Chalmer’s “hard problem”. John Locke (1632 – 1704) complicated matters farther with his concept of personal identity.

Given the apparent complexity of consciousness it is understandable why any discussion defining and understanding consciousness skews toward the metaphysical, or if approached from a scientific perspective, leaving the definition dangling with unknowns.

A Detour Through Science

To keep our discussion and definition of consciousness on a scientific basis, let’s take a side tour to a scientific model of reality that has a few dangling unknowns of its own. The point being that, dangling or not, a scientific approach is the closest we can get to a mutually agreed upon reality. We can be fairly certain that new discoveries are waiting to be made to shed light on what is not known. It is the approach toward that knowledge that is really more important than the knowledge itself. For example, the physics of time.

Why Broken Eggs are Never UnBroken

The second law of thermodynamics is basically about the flow of energy (heat). It is really the foundation of our perception and measurement of time. Entropy is the measure of how disordered or dispersed energy within a system is arranged. Enthalpy describes the energy in the system. We are focused on entropy.

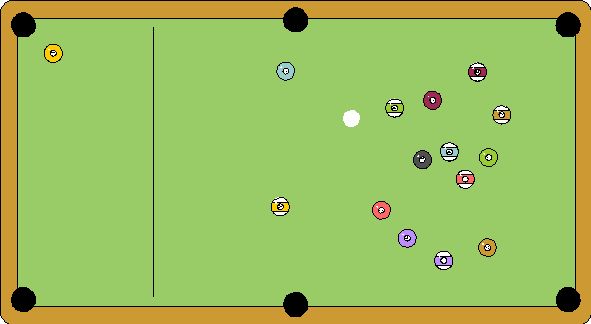

Billiard balls on a billiard table are a good way to illustrate entropy. Billiard balls haphazardly scattered on a billiard table is an illustration of high entropy where the billiard table is the system and the balls are the elements in the system potentially available for work. The work might involve falling into a pocket hole where it triggers a lever to initiate another action like triggering another lever.

For our purposes, the point is that the balls are scattered across the table. Entropy. The balls are not as readily available for work as they could be if they were racked or lined up in a row. This would not mean that the system has no entropy but rather it has less entropy than it could have. Scattered balls equal high entropy, ordered, line up balls equal relatively less entropy.

What does this have to do with a definition of consciousness?

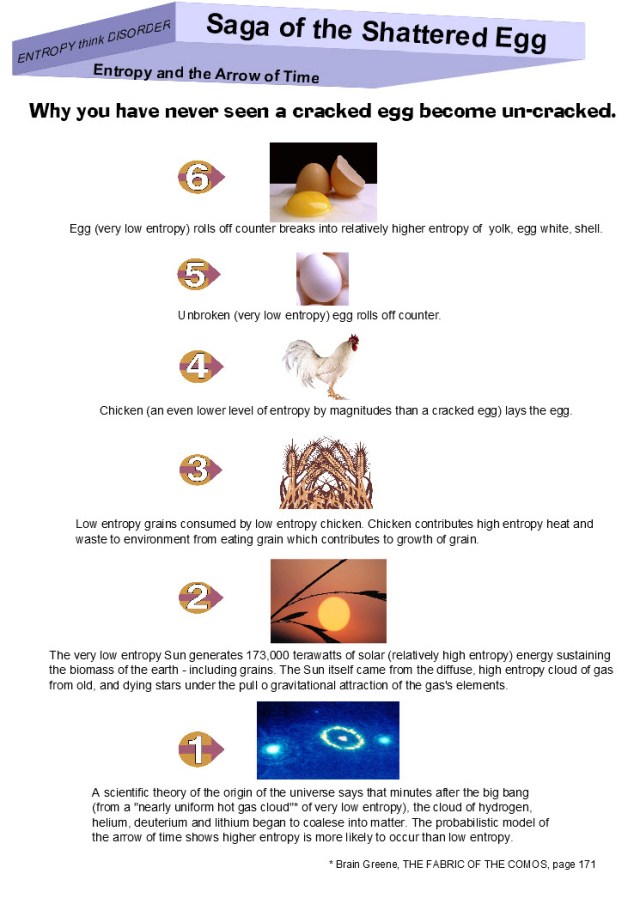

At this point, a related question is whether you have ever seen an egg roll off a counter, shatter and splatter on the floor and then re-assemble into an egg again? Living in the same universe as most of us, the answer is no. The egg goes from a low entropy system (a formed egg with precise potential energy) to a higher entropy system (shell, yoke, egg white lying on the floor in another system we refer to simply as the environment). There is no logic or axioms in the physics of thermodynamics saying that an egg could not spontaneously re-assemble after breaking. But we have a very good scientific reason why it will most likely never happen and has everything to do with entropy.

Let’s take a deep dive into our side tour.

Reality Knowns and Known Unknowns

In chapter six of The Fabric of the Cosmos3 titled “Chance and the Arrow “, Brian Greene provides an amazing explanation of the arrow of time involving eggs and ice cubes.

How does an egg end up scattered and broken on a floor? A force pushed, pulled or dropped it. Why does it end up scattered and splattered on the floor? Because the forces holding the egg together are not strong enough to withstand the forces causing it to shatter and splatter. Well, after the egg has fallen to the floor, why can it not simply re-assemble to the shape and form it was after the force is no longer acting upon it?

It is this latter question that Greene answers conclusively. It is not that the egg cannot re-assemble into its former self, it’s that the probability of it happening, the probability of us ever seeing a shattered egg re-assembling is so low that we consider it an impossibility. But it’s not.

The egg that shattered, the egg from the chicken that laid it, the feed that provided the food to nurture the chicken, to photosynthesis from the Sun radiating energy enabling the grains to grow, to the cosmic gas cloud that condensed to form the Sun, to the “big bang” that gave rise to the cosmic gas composed of elements and gravity that resulted in the sun resulting in our shattered egg.

Greene shows that space-time is pretty much a one way street. The reason it’s a one way street is because we see the universe going from an incredibly low entropy state (the big bang) to an increasing entropy state where minuscule elements–suns, dust, planets, rocks–clump together into relatively lower states of entropy until they disintegrate again into high entropy. Greene uses this nice phrase to describe what we currently see in the universe. He writes, “the current order is a cosmological relic”.

So the simple reason we never see a shattered egg reassemble is not because it’s an impossibility. The probability of it happening in a university evolving in space time from low to higher entropy goes against the flow of the universe.

The Fungus Amongst Us

What does entropy and the cosmological theory of the big bang giving us the origin of the universe have to do with a definition of consciousness?

The point here is that stepping backwards through one of the laws of classical physics we arrive at an unknown. The big bang. The big bang theory of the creation of the universe may or may not be correct. But right now the laws of classical physics work quite nicely with the theory. It is science.

Now, suppose we apply the same science based, logic trace to arrive at a definition of consciousness?

Two things here.

First, note that we did not include intelligence as an attribute commonly attached to a definition of consciousness. That does not mean there are no scientists or philosophers who do not include it. But intelligence, strictly speaking, is an attribute denoting the ability to apply skills to solving challenges of survival or just problems in general. According to Paul Stamets, citing a result from research in 2000 by Toshuyiki Nakagaki, in his 2005 book, MYCELIUM RUNNING(4), fungus demonstrates the intelligent ability to seek and find substance (food). If an expanding fungus can navigate a petri dish to find the quickest path to sustain its existence, that certainly demonstrates intelligence. Intelligence measured in degrees can apparently go from an Albert Einstein to mycelium (basically mushrooms), to scavenging cockroaches instinctively (or perhaps intelligently) scurrying away from light.

Secondly, there is artificial intelligence and the–what? hope, dread, fear–that machines or robots will become so intelligent that they will acquire consciousness. This belief of course surfaces without having a definition of what constitutes consciousness–only the process by which consciousness is observed. But in the case of artificial super-intelligent robots, the anticipation is that the machines acquire so much knowledge that they start making value judgements. Value judgements. Remember that phrase. What will these super-intelligent machines do once they have acquired all the knowledge stored in every library in the world?

For reasons (mostly unspecified, or loosely specified) super-intelligent robots would make their first order of business the eradication of humans. Looking at this from a purely scientific view, considering the law of thermodynamics and the useful energy humans contribute to the environment juxtaposed with their excessive consumption of the environment’s available energy, eradication might be a very logical option. So, once these super-intelligence machines have acquired all the knowledge available to humans and even extrapolated that knowledge beyond anything a human could conceive, and have eradicated humans from the planet. What do they do next?

Being super-intelligent machines they would most likely gather on a beach in Santa Monic and wait for the Sun to turn into a red giant, engulfing all life on the planet. This is what a super-intelligent human would do especially since there would be no other humans around.

Note that nothing these robots could do, from eradicating humanity to digesting and extrapolating all the knowledge in the world, is not anything any human could not do. Intelligence as a prerequisite for unraveling a definition of consciousness, like the other four attributes listed at the beginning, is merely an attribute, a description of consciousness, but is not a definition.

So we leave our side tour into the scientific method that can arrive at scientific, empirical reality even though it may be derived from an unverifiable theory of reality. We are on treacherous ground. But the science is the science and despite its shortcomings, science gives us reality. Which, of course, brings us to neurology–the science of the brain. A hard reality befitting a “hard problem”. When it comes to neurology, science has a theory. Sort of like the big bang. Think fungus.

© Lynard Barnes, 2020

Leave a Comment