The Definition of Consciousness

Me, I, My and Us, the MIMU of Self

BY LYNARD – MAY 15, 2022

The Nomenclature of Dreams

If someone asked what thought was going through your head an hour ago, not what you were thinking about but the actual thought you had, you would be unable to answer. The same would be true if asked what dream you had five or six days ago. Dreams are supposedly hallucinations. Thoughts are not. Yet, they share this one intriguing peculiarity of not being subject to recall. At least, not recall in their pure, unadulterated form.

Neuroscientists know why dreams are not easily recalled. During dreaming-sleep (rapid-eye movement- REM sleep), short-term memory is completely shut down. If a dream is not documented immediately upon awakening, the events of the dream are seemingly lost forever. Is the same true for daily thoughts streaming through wakefulness. We impulsively want to say No. Objective reality says otherwise.

The curious similarity between dreams and a thought does not end with the lack of ability to recall. During dream-sleep, two or three dreams may wisp-by and there is no short-term memory to store them. There is no gatekeeper to shift through content for importance or relevancy. In wakefulness, thoughts stream into awareness (memory), and are selectively removed or combined into the thought stream (memory storage). The gatekeeper, the executive frontal lobe, must decide what is and what is not significant enough to merge into the stream of self-awareness and situation-awareness. (Where does this adjudication process come from?) One thought can easily and smoothly blend into the stream of thought before and after it. There can be no recall of a single thought. Single thoughts simply do not exist. Memory does not allow it. Dreams, on the other hand, are like orphan thoughts caught between a point of origin and their dissolution into a vague, emotive status. You can write down a thought and make a record of it. You can also do the same for dreams. In both instances, especially with a single thought, there is an oddity, a strangeness to it without the context and stream of thoughts from which it is plucked. The same can be said of dreams.

There is one other peculiarity of dreams exemplifying their place in our wakeful-thought life and the definition of consciousness.

Babies and Rational Human Beings

Newborns spend some 70 percent of their time asleep–16 to 18 hours a day1. If rapid eye movements (REM) are indicators of dreaming, babies (1-2 years) spend over 50% of their time sleeping and “dreaming”. According to some researchers, these “dreams” are not visual or auditory representations of the physical world. Rather, baby “dreams” are merely electrical activity of the brain emulating what we think of as the dream state. Which raises a question: has anyone ever asked a baby if their dreams are pictorials?

According to this research, it is not until a child reaches seven or nine years of age do dreams become “delusions” or “hallucinations” disguised as reality. Of course, assessing the validity of this research is like the toddler in the grocery store shopping cart discussed in PART IV. The baby in the cart stares at you with puzzlement as you stare back. Ask the baby what they are thinking, they will simply continue to stare with their usual look of bafflement. They would most likely have the same reaction if asked whether they dreamed in pictures.

Dreamland would be a perfect world for infants. A dream has no beginning. A dream has no ending. You drop into the middle of a situation, a tad bit of nervousness or apprehension perhaps, observe and participate in some activity, creating dialog and sounds where appropriate. You then awake from the dream with a vague memory of something having happened.

Four Thousand Excursions into Altered Reality

After classifying more than 4,000 of my dreams I side with neuroscientists on sleep being an altered state of consciousness. The key feature of consciousness, intrinsic to use of the word by neuroscientist, is our ability to make executive, self-directed decisions about activity and thought. Thus, sleep is not consciousness. Researchers have found that conscious activity can intrude in flashes upon sleep so sleep is not a continuous state. Conscious activity can also intrude and quickly recede even in a state of dreaming.

After having a dream and recording it, I would sometimes stop and ask how much rationalization (conscious filtering) was creeping into the narrative. Micro-flashes of self-awareness usually preceded waking up to record a dream. The dreams I recorded, 78% of them, were of events which were mostly logical and sequential in content. When compared with the dreams of others, my dreams seemed too logical, seemingly too realistic. I think I have an explanation for this and it has to do with the very act of recording dreams.

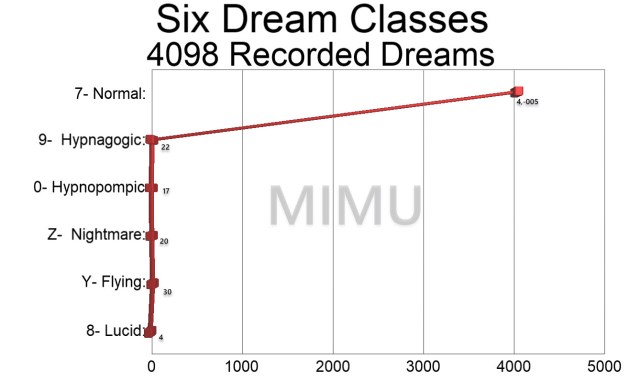

Six Classes for Six Questions

Below I examine the classification scheme I devised for examining 4,098 of my dreams recorded between 1975 and 2021–forty-six years. The actual number of dreams recorded during this period was 5,096. However, 996 were eliminated from classification because they lacked a clear subject or action predicate. For instance, “I dreamed I was in a park.” has a subject but no action predicate. “Ran from a pack of dogs”, is an action predicate but has no dream subject. (What “park”? when? where?) The action predicate is the most important aspect of my classification scheme. The action predicate is where an emotion is generated and dreams are all about emotion.

All 4,098 dreams were put into one of six categories:

When classifying data the objective is clarification. Obviously when 97% of your data falls within one category and your data is dreams, there is not much clarification.

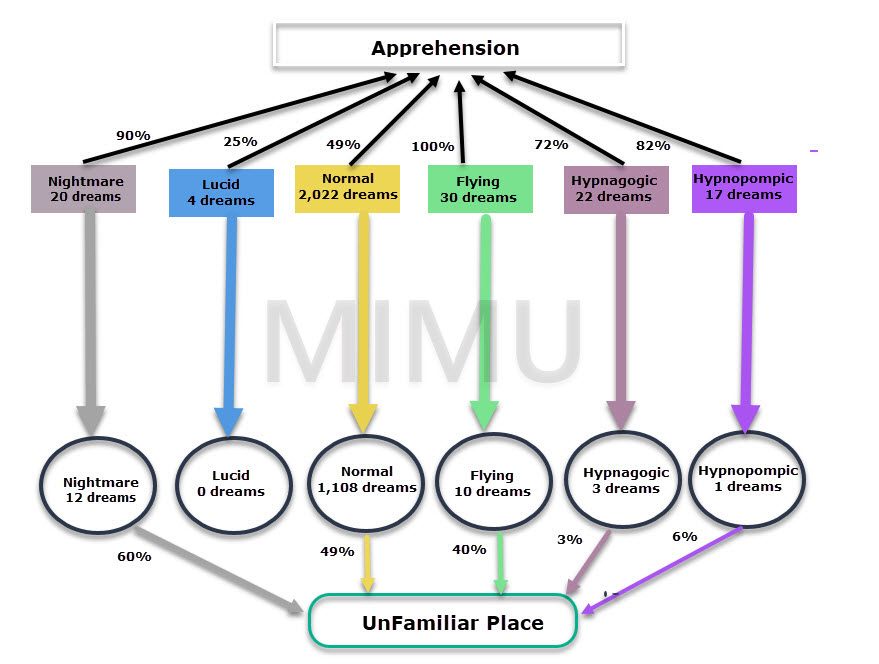

In November 2018, before I decided to come up with a classification scheme for my dreams I dreamed about coming up with a classification process. At the time I was not really thinking about categories and classes. My focus was on word-tracking associations. In the dream about classification (#3513# recorded in 2012) I was frustrated by how difficult it was to come up with a viable scheme to classify dreams. Was this a predictive dream? Not really. Fitting into the category of Normal dreams, the anxiety dream about classification shared the emotional qualities of apprehension, fear and annoyance common to 63% of all six categories of dreams. For our purposes here, the 4,005 dreams in the Normal category reveals a map into the opaque world of self as an independent agent.

Answered Questions From Dream Records

The six categories I used for dream classification clarified and answered a few questions I had about dreams since I began recording them.

How many times have I had a recurring dream?

There is a popular belief that we have dreams which recur. In a previous interlude (PART VI) I related the instance of what I thought was the recurring MESSY HOUSE dream. In my case, I found the idea of a recurring dream actually occurred within the dream itself. There were three instances in which my dream-self remembered having the same dream before. A variation of the recurring dream was memory within the dream of being in the same place (a store) before. There was nothing in the dream records to support either a recurring dream or having been in a dream place before despite the conscious belief to the contrary. It is entirely possible the dream element–store or house–occurred in a dream that was not recorded but I have strong doubts about this take.

Why did so few of my dreams contain spoken language, sometimes a foreign language I did not understand while awake but understood perfectly when dreaming?

The distinction between spoken words in a dream and simply thoughts being transmitted and received was of special interests. In some dreams I heard words spoken and other sounds. This was unusual for me and, from research by others, is a rare occurrence. Most research involves attempts to determine how external sounds are incorporated into dreams. Little research is available about sound generated from within dreams. If you think about it, carrying on a dream conversation in which you are generating dialog for everyone is the prototype of a hallucination. What about the auto-directed conversations we carry on daily in our heads? Roughly 13% (548 entries) of my dreams contained sounds or spoken words.

The distinction between spoken words in a dream and simply thoughts being transmitted and received was of special interests. In some dreams I heard words spoken and other sounds. This was unusual for me and, from research by others, is a rare occurrence. Most research involves attempts to determine how external sounds are incorporated into dreams. Little research is available about sound generated from within dreams. If you think about it, carrying on a dream conversation in which you are generating dialog for everyone is the prototype of a hallucination. What about the auto-directed conversations we carry on daily in our heads? Roughly 13% (548 entries) of my dreams contained sounds or spoken words.

Why do I occasionally hear music in my dreams?

Like spoken words and other sounds, music was heard in very few (1.8% or 74) dreams. Only in one instance was the music pertinent to the content of the dream. In most of these dreams the music was background sound.

What was the usual dream context in which I had dreams of flying?

As J. Allan Hobson points out in his book DREAMING: A Very Short Introduction[17], Sigmund Freud regarded flying dreams as disguised “unconscious” sexual desires. I recorded 97 dreams explicitly involving sexual activity. None involved flying. The popular “dream interpretation” assessment is that flying dreams are moments of spiritual freedom. Of my 30 flying dreams or floating above a scene, all involved moving from point A to B or moving beyond an obstacle or danger of some sort. In one flying dream (#4840) my dream-self willed my body to fly and skim over the top of trees knowing people below were watching in amazement. I suspect that there is a strong biochemical basis for dreams of flying. The same is also most likely true for dreams of falling. Flying are dream events, not emotions. Events generate emotions.

As J. Allan Hobson points out in his book DREAMING: A Very Short Introduction[17], Sigmund Freud regarded flying dreams as disguised “unconscious” sexual desires. I recorded 97 dreams explicitly involving sexual activity. None involved flying. The popular “dream interpretation” assessment is that flying dreams are moments of spiritual freedom. Of my 30 flying dreams or floating above a scene, all involved moving from point A to B or moving beyond an obstacle or danger of some sort. In one flying dream (#4840) my dream-self willed my body to fly and skim over the top of trees knowing people below were watching in amazement. I suspect that there is a strong biochemical basis for dreams of flying. The same is also most likely true for dreams of falling. Flying are dream events, not emotions. Events generate emotions.

What is the difference between the paralysis state experienced before sleep (hypnopompic) and after sleep (hypnagogic)?

For me in both paralytic states the central feature were terror, fear and curiosity. My first recorded hynopompic experience occurred in November 1975 (#4989) and the first hypnagogic experience in November 1993 (#2810). I have always compared these paralysis episodes with the alien abduction narratives reported by author Whitley Strieber (Communion: A True Story by Whitley Strieber18) and especially the alien abduction narratives reported by Raymond E. Fowler in his book The Watchers II19. My paralysis episodes involved all the “intruder” elements of reported abductions–little people whispering incomprehensible words. There were no abductions. After experiencing roughly half of the thirty-nine paralysis episodes, I have come to accept them as alternate states of self-awareness in which profound though not extraordinary psychological effects occur. Reportedly, 6.6%20 of the general population experiences sleep paralysis. Paralysis experience surrounding sleep are undoubtedly organic in origin–determined by bodily chemical and electrical functions. I am convinced these paralysis states are associated with some form of transitory, as in organic, emotional depression. Neuroscience speaks of reduction of reaction time in the frontal lobe. There is no reason to doubt this assessment. But there is more than just a neurobiological based emotional condition involved. Personality traits and personal expectations color both hypnopompic and hypnagogic experiences.

Dreams as Reality Constructs

In PART 4, we discussed standing in a line observing a toddler in a parent’s shopping cart. We wondered exactly what the child saw when observing the stranger in front of them. Since the child can not verbalize what they see or feel, you rely on your internal dialog generator to verbalize what the child might be thinking. You do not hallucinate. You use your imagination. Is using your imagination the same as hallucinating? No. Because you, that frontal lobe executive managing memory, controls your imagination, keeps it within rational bounds. You can drop back into the reality of the moment at any time. Observing a silent infant sitting in a shopping cart for instance.

In PART 4, we discussed standing in a line observing a toddler in a parent’s shopping cart. We wondered exactly what the child saw when observing the stranger in front of them. Since the child can not verbalize what they see or feel, you rely on your internal dialog generator to verbalize what the child might be thinking. You do not hallucinate. You use your imagination. Is using your imagination the same as hallucinating? No. Because you, that frontal lobe executive managing memory, controls your imagination, keeps it within rational bounds. You can drop back into the reality of the moment at any time. Observing a silent infant sitting in a shopping cart for instance.

This seemingly off-topic subject of babies and what they may or may not be thinking at any given moment will pop up again as we define consciousness. Here it is relevant because the situation has a component common to dreams. Like a dream, you encounter a person, the baby, for whom you could create your own dialog. You may ignore the child. If not you may create a brief dialog in your head. You have a life in which reciprocal dialogs do not depend upon your own thoughts. This broadly comes under the jargon of the Theory of Mind–we assume the person we encounter share our own emotional and mental capacities. The key point here however is that you recognize that the baby in the cart could carry on a dialog if they could speak and were so inclined.

If mature human fetuses (24 weeks and beyond) spend time dreaming, the question is why? Certainly they don’t have taboo unconscious urges requiring symbols to be interpreted. They could be processing and assimilating tactile and sound information from their physical environment. But then this raises an origin question. Which comes first for the fetus: processing or stimulus assimilation?

Given the amount of time infants sleep and presumably dream, it is not unreasonable to assume that dreams are about the future, not the past. Fetuses, as far as we know, have no pass. Only a future. Our focus on the imagery, mentally constructed tactile sensation in dreams deludes us into believing dreams are about yesterday, the day or years before. Or we hypothesize that dreams are about consolidating memory, rewriting moments of wakefulness in symbolic form. In reality–read that as in the moment– dreams are the scaffolding on which the future of wakefulness are built. The process is a continuum. The real question is how do dreams differ from the stream of thoughts we have while awake. A significant clue lies in the dreams examined.

The only dreams I had in which there was no element of apprehension, anxiety, fear, anger or annoyance were the four lucid dream experiences. Some level of apprehension or related emotions are such an integral ingredients of dreams that it is impossible to separate the two. Think of the momentary pause you make in crossing a busy street. Or, imagine the experience of a fetus being born into the world of air and tactile sensations. Dreams are the scaffolding on which tomorrows are built, cauldrons distilling what we will be in the future.

In order for neuroscience to come up with a scientific definition of consciousness as self-awareness, not only for humans but possibly a host of other species, it will be necessary for the science to back away from the blunt electro-biochemical brain model they are currently using. Backup or dig deeper. Maybe dig all the way down to the world of quantum uncertainty. Humans–life itself–may be a biochemical machine but it is a machine running on a fuel of which we are totally unfocused.

REFERENCES

* Based on roughly 3,270 records from 2010 to 2021 which is not the entire period covered by the dreams examined.

# This symbol refers to the record number identifier assigned to an entry in the dreams database and is not a sequence number.

16. THE WASHINTON POST, February 6, 2022, Carolyn Wike, Copyright 2022, originally published by KNOWABLE MAGAZINE.

17. DREAMING, A Very Short Introduction, J. Allan Hobson, Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0-19-280215-6

18. Communion: A true Story, Whitley Stieber, Avon, 1987, ISBN: 978-0-380-70388-3

19. The Watchers II, Raymond E. Fowler, Copyright 1995, Wild Flower Press, P.O. Box 726, Newberg, OR 97132, ISBN 0926524-31-3

19. Mental Health Daily, https://mentalhealthdaily.com/2015/05/18/hypnopompic-hallucinations-causes-types-treatment/

20. Zlatev, Jordan, Racine, Timothy P., Sinha, Chris and Itkonen, Esa. “The Shared Mind: Perspectives on Intersubjectivity: Converging Evidence in Language and Communication Research 12”. Cognitive Linguistics Bibliography (CogBib). Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, 2010. https://www.degruyter.com/database/COGBIB/entry/cogbib.13335/html. Accessed 2022-02-13.

Leave a Comment